Over the past few months I have watched my friend craft her death like a work of art. It is nearly complete.

She started with abundance. She spent frequent weekends watching her beloved grandsons compete in athletics events. (She was a runner for years – she told me she started running to beat breast cancer the first time it sneaked up on her.) She cared for her mother, at first in her home; later, after her mother moved into a facility, through daily visits and outings. She volunteered all over town – at the Cancer Center, the library, our church, a low-cost clinic. She traveled and went on a cycling tour.

She had a fat orange kitty named Peaches. In summer, her garden was full of roses. Her home was always immaculate, and friends were always welcome. Every day she ran or cycled, except on the worst days of chemotherapy. On those days, she walked. Every single day, summer and winter, busy day or not, her alarm woke her at 6.00AM, and every single morning she spent an hour or more in prayer and quiet, thoughtful study of her Bible.

Her mother died last year, and some months after that the doctors told my friend they had worked through every treatment option available and had nothing left to offer her. Then Peaches died early this year. My friend kept right on volunteering, running or cycling daily, waking at 6.00AM, welcoming friends, tending her roses, seeking to know God better.

And day by day, stroke by stroke, using her disease as a chisel, God carved away her life.

Or so it seemed to me. Only, when I started really paying attention, I understood that something different was happening. I watched how she stood before her God and He said, “Will you give me that?” and she said “Yes” – so that running gave way way to walking, striding for miles gave way to a careful stroll down the block leaning on a walker.

He asked and she yielded – the library, the clinic, the Cancer Center, church activities, traveling to be with family, working in her garden. She stopped driving and depended on friends to take her shopping, and then to do her shopping for her.

Having been always quietly, insistently independent, she let her neighbors mow her lawn, take her garbage to the curb, collect her mail. Hospice sent someone a few times a week to help her bathe. Then they started sending someone to help her get ready for bed in the evenings and do a bit of cleaning, although she fixed her own dinner. A few weeks ago she started having a caregiver with her all night, but she still got up at 6.00AM every day so she could be dressed and see them through the door in plenty of time to sit down with her Bible after breakfast, just as she had always done.

“Are you afraid?” I asked her once. It was not a foolish question. I watched her closely and never saw her flinch, so I thought maybe I was just too stupid to understand. She thought about it, then said, “I’m afraid it might hurt. And I worry about losing my dignity.” That evening while I was helping her get ready for bed (it was a Sunday, when she sought the help of friends rather than the folk Hospice sent), as she leaned forward she farted. It was loud and unexpected and we were both startled, and it was entirely impossible to pretend it hadn’t happened. “Well, there goes your dignity,” I said at last, and we both fell about laughing.

Her liver failed. Her features have always been sharply chiseled with strong, prominent bones. She yielded her profile and it sank into puffiness. She yielded her clear, direct gaze as her eyelids swelled and she became too weak to open her eyes wider than slits.

Last Saturday Hospice sent her a hospital bed. We watched a movie – “The Gods Must Be Crazy” – while we waited for it to be delivered. I massaged her feet and told her how that movie had inspired me to abandon my own career as a journalist and start a mission school in a rural village in Africa. She ate a shortbread cookie.

On Sunday she was tired and weak. She wouldn’t eat, and spent much of my visit in her new bed, sleeping while I read my book in the chair she had bought for visitors. Her son called, but she couldn’t speak without slurring so he asked her to give the phone to me. He told me he planned to drive over on Thursday. I hesitated, then said, “Not until then?” I heard his breath catch. “Oh,” he said. “I’ll be there on Tuesday.”

On Monday she was alert again, happy at the prospect of seeing her family. She knew the lift in her spirits would be short-lived, so she told Hospice she was ready to go onto 24-hour care. We sat in the living room and watched another movie – “As Good As It Gets” – and made plans to take a drive, get her out of the house, just as soon as the weather improved a little.

On Tuesday she couldn’t walk further than the distance between her bed and her toilet. She drank from a little sponge on a stick that she dipped into a cup of water. I learned that she hadn’t been able to sit up to read her Bible for a few days, so I sat beside her bed and we flipped through Psalms, and I read everything she had highlighted – her trove of prayers and promises. Sometimes I thought she was asleep, but whenever I stopped reading she opened her eyes, so I would carry on.

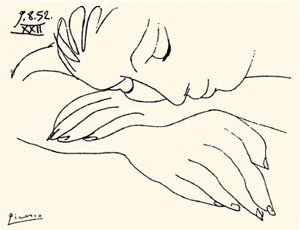

Yesterday morning I looked at her lying on her bed, as insubstantial as a quick sketch in soft pencil. She has peeled away and yielded all the rich clutter of her life on earth, and what’s left is the pure essence of a woman whose trust in her Maker’s love has not wavered.

I finished reading the Psalms and, at her request, started 2 Corinthians. I have promised to continue today, but she did not promise to wait for me to come.

Your friend is a special woman. And she has a special woman for a friend.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you. She is very special. I’m going to miss her dreadfully.

LikeLike

Wow! Thank you for this. What an inspiring life you have painted for us so beautifully with your pen. The old picture of the sculptor in the stonemasons yard of rejected chunks of stone. When asked what he planned to do with it, he said something like this: “I can see an angel trapped in the stone and I am going to chip and file away all that is not the angel, and so give her, her wings, and set her free.” We are all in the great Stonemakers shop, and with heavy blows and gentle strokes He is working on us to set us free to be what He sees us to be.

Keep it up Val/Belladonna?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Deej…:) I have learned so much about how to live from watching her die. And while I have often been sad, the most striking thing to me has been the beauty in her calm, quiet, trusting endurance.

LikeLike

Beautifully written. And what an amazing job you’ve done at capturing the essence of your friend in just a few words.

Pre-parenthood, I used to work for Hospice as a reiki practitioner. It was and is the most meaningful and inspiring work I’ve ever done. There is something about spending time with those close to death that lets us see the beauty of who they really are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Lindsay…:) It’s good to hear you confirm what I’ve seen – that her experience is not unique. I know – at least, I assume – that physical suffering and emotional turmoil must often make death a painful and difficult process. This is the first time it’s ever occurred to me that it can be beautiful. Walking alongside her has affected me in ways I haven’t yet had time to explore.

LikeLike

Utterly beautiful. Your words, her, and you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, my friend.

LikeLike

I am overwhelmed by the tenderness and insight here.

So lovely.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. It was so hard to write, and I still feel – of course – that I’ve failed to express what I set out to say. It’s encouraging that you and others understand anyway.

LikeLike

This was awesome. Thank you so much for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I really appreciate you and everyone else who has stopped by and taken the time to comment. This was a tough one to write.

LikeLike

beautiful words. Thank you so much for sharing with us

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for commenting. I’m glad this story touched you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is the first piece I have read of yours, and it is soul touching beautiful. Thank you for sharing such a beautiful glimpse into your friends (and your) spirit. Truly remarkable.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for reading, and for the words of encouragement. Also for following…:) I’ve been loving getting to know you through your blog too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Heartbreakingly beautiful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you…:) Also thanks for the follow. It feels good to know real people are reading what I write.

LikeLike

Sorry for my late discovery. I’ve been the worst at blogging (reading and writing) lately. Looking forward to reading more of yours.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This post reminds me a lot of someone I knew who was also so brave in the face of death. Thank you for telling her inspirational story of emotional strength.

LikeLike

I’m so glad it meant something to you! Thank you for stopping by, and for commenting.

LikeLike

Deeply moving posts.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Tammi – and thank you for following. I’ve been out of action for a while but should start posting again very soon. It’s good to have you on board.

LikeLike